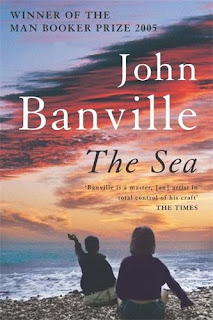

Paul Stewart Reviews John Banville's The Sea

So, John Banville has finally won the Man Booker Prize. But why has this long-awaited recognition come with The Sea, rather than with Eclipse, Shroud, or The Untouchable? The question arises because Banville has long been mining a familiar stylistic and thematic seam. One can almost make a check-list of a Banville novel. Is it a confessional narrative? Yes. Is the narrator highly erudite and emotionally crippled? Yes. Are there memories to be re-configured through the prism of a startlingly beautiful prose? Yes.

In short, The Sea is the epitome of a Banville novel.

Max Morden, the narrator, is, as in The Untouchable, an art historian (allowing for some stunning application of the uxoriously obsessive work of Bonnard), revisiting the quiet sea-side community of his childhood after the loss of his wife, Anna, to cancer. The summer when the young Morden encounters the Grace family – eccentric farther, casually seductive mother, the twins Chloe and the silent Myles – is the main memory with which Morden struggles. Comparisons to Proust are inevitable, if perhaps unhelpful. Recollection might be sparked by the seemingly inconsequential, but Banville knows that memory is a witness that cannot be sworn and that it is an unreliable bolt-hole. As Morden puts it: “… the past is just such a retreat for me, I go there eagerly, rubbing my hands and shaking off the cold present and the colder future. And yet, what existence, really, does it have, the past? After all, it is only what the present was, once, the present that is gone, no more than that. And yet.” This “and yet” is what powers the novel.

The unreliability of memory allows for some nifty plots twists, but these concessions to story take second place to the shifting patterns of the narrators re-configuring of the past, enlivened throughout by Morden’s mordant comments. With the drawn out death of Anna now already past, we realise that memory is the only levee we have against death, and it does not hold: “We carry the dead with us only until we die too, and then it is we who are borne along for a little whiles, and then our bearers in their turn drop and so on into the unimaginable generations.” Despite the bulwark of memory, the sea as death inevitably overwhelms all such man-made defences.

One cannot escape Banville’s style; nor would one wish to. It is, as Martin Amis pointed out, a “sensual delight”, but that delight is more than a spine chilling thrill at the decorousness of a literary language. In the passage just quoted the work the words are called upon to do is extraordinary. With a regard to primal words that would make Freud proud, the passage both delicately and indelicately balances the metaphor of carrying with that of (as Samuel Beckett would have had it) “birth to into death.” At our death we are “borne” or “born” into an afterlife of remembrance. When those who carry our memory themselves “drop” dead, they drop that which they have borne; their memory of ourselves. The simplest of words, “drop” and “borne”, bear the weight of this death-dealing delicacy; a delicacy which borders on the indelicate when we wryly smile at the joke lurking within that “drop.”

With the first person narration, the examination of a life of and through memory, the beauties of an exact style, it would appear that I could have been describing Eclipse or The Untouchable. That Banville is a one trick pony is an oft-levelled criticism; a criticism, incidentally, not directed at Beckett, one of Banville’s closest precursors, in whom such singularity of purpose is admired. Such a criticism is ultimately unsatisfying, whilst enjoying some accuracy. Banville does mine a narrow seam; but that seam unerringly hits gold. If we are to think of Banville’s artistic focus, Max Morden provides the means to do so. His favourite artist is Bonnard, who painted countless portraits of his wife in the bath. After her death, the portraits continued from memory. In contrast to Morden, Bonnard is a real artist, “…the real worker [for whom] there is no finishing a work, only the abandoning of it. A nice vignette has Bonnard at the Musée du Luxembourg with a friend … whom he sets to distracting the museum guard while he whips out his paint-box and reworks a patch of a picture of his own that had been hanging there for years.” Over the past few novels, with a restricted but finely honed palette, Banville has set about working and re-working his art. In such terms, and as The Sea attests, Banville is a real worker.